Infinity Dance Theater and Alison Cook Beatty Dance

The Riverside Church Theatre

New York, New York

June 28, 2019

Touched by Fire, Ghosts in the Machine, Mahaway: Spring Eternal, Pietà

A long time ago, in a city far, far away, I cut some of my dance-going teeth on performances at The Riverside Church Theatre on Manhattan’s Morningside Heights. It’s been more years than I care to mention since I’ve been there, but I still remember certain pieces I saw there vividly, including what I recall as one of the best choreographed iterations of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, performed by the Joyce Trisler Danscompany. I returned to Riverside Church Theatre last Friday for a combined program by Infinity Dance Theater and Alison Cook Beatty Dance, and found that despite the considerable passage of time, some things don’t change. The program, under the overall heading “Ghosts in the Machine,” was memorable – not only for the dances presented, but for the courage, respect, and affection that permeated the atmosphere. That it included a piece that had been created in commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the premiere of The Rite of Spring, was icing on the cake.

I’d seen Alison Cook Beatty Dance once previously, on a shared program this past spring at New York Live Arts, and although I didn’t find the piece a complete success, was sufficiently impressed with Artistic Director Alison Cook-Beatty’s choreography, as well as the caliber of her company’s dancers, that I was eager to see more of her work. On the other hand, I had not previously seen or heard of Infinity Dance Theater (even though it’s been in existence for nearly a quarter century). If I had, or if I’d read the accompanying publicity release, I’d have known in advance that the company, under the leadership of Artistic Director Kitty Lunn, presents pieces primarily created for, and performed by, persons with physical disabilities whose movement range is severely limited and/or accomplished by wheelchair. As soon as I walked through the church door, however, and saw people with smiles on their faces even before the performance began, I knew I was going to see something different from what I’d anticipated.

I’ve seen programs before by companies that provide dance opportunities for the physically disadvantaged, and although I’ve found them admirable, the programs didn’t go beyond that. This program did. It consisted of four pieces: two were revisions to previously choreographed Cook-Beatty pieces, and a pair of world premiere dances choreographed by Lunn.

The opening piece is a statement, and set the tone for the evening.

Cook-Beatty originally choreographed Touched by Fire as a solo, but modified it last year as a duet for herself and Lunn. The program indicates that this is “Version C” of the piece, so I suspect that there was at least one other prior incarnation as well, but having seen the version on this program, I have difficulty visualizing it any other way.

Prior to the dance’s beginning, the stage is set with candles forming a rough kidney / oval shape on the stage floor, which is otherwise bare. The candles provided the brief dance with an appropriate sense of reverence, which carried to the choreography itself. To J.S. Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major, played live downstage left by Sam Bae, Cook-Beatty and Lunn at first are seen in parallel positions, moving in sync with each other despite Lunn’s being in a wheelchair.

The connection between Lunn and Cook-Beatty soon went beyond tandem arm motion. Their hands connect, and then Lunn rises from her wheelchair and takes a step or two toward Cook-Beatty, then both quickly assume parallel kneeling position on the stage floor. After Cook-Beatty moves the wheelchair that Lunn had been confined to aside, they roll on the floor (again, parallel to each other), and then Cook-Beatty pulls Lunn around the stage floor – as in transporting her rather than coercing her. After Lunn returns to her wheelchair, and Cook-Beatty to a reclining position on the stage floor, they reach toward each other and touch their hands – a la Michelangelo. The piece ends with both Lunn and Cook-Beatty standing in the same parallel position as they were when the dance began, but with Lunn standing.

My description cannot begin to adequately describe the power that this brief introductory dance demonstrates. What it shows, and what it indicates will be on display throughout the evening, isn’t just collaboration; it’s a mutuality of respect. And the images that Cook-Beatty’s choreography and their performances transmit, even given the dance’s brief stage-time, are indelible.

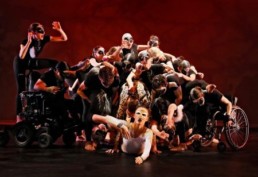

Lunn’s Ghosts in the Machine, choreographed to Maurice Ravel’s Bolero, is inspired by Ravel’s comment that the music’s driving rhythms were inspired by a factory he visited with his father, an engineer. I checked, and indeed Ravel is said to have based the piece’s rhythm on the sounds of a factory. [He also said that the Bolero’s melody was inspired by a song that his mother would sing to him at night.] Ravel’s composition, intended to be the score for a ballet, premiered in 1928 with the Ballets Russes, with choreography by Bronislava Nijinska; it was set in a Spanish Tavern, where, as the music evolves, a woman seductively dances to the music on a table top.

After that premiere, Ravel reportedly said that unlike the stage treatment originally provided for his composition, his ideal setting for the piece was in the open air, with a factory, presumably including its machines, in the background. Lunn’s concept is in line with Ravel’s preference.

When Ghost in the Machine begins, images of huge factory machines of various sizes and shapes are projected against the rear scrim, and as the composition unfolds, one can almost see the machines whirring in tandem with Bolero’s pulsing beat, and coughing and belching with emphasis at the conclusion of each melodic themed sequence. Lunn’s visualization of Ravel’s score seems to emerge from that background.

Aside from the progression of wheelchairs (and of dancers with functioning legs) that provide a sense of movement across the stage, most of the visual energy that amplifies Ravel’s beat is accomplished by the performers’ arms. That description might give the impression that Ghosts in the Machine is relatively static, but the opposite is true. It’s a vibrant piece, with the performers in constant motion either crisscrossing the stage or within a narrower, more confined physical area. And, like Ravel’s composition, the dynamism increases as the dance progresses. After awhile, you almost forget that these performers are, predominantly, in mechanical contraptions that enable them to move.

And that fact, the mechanical nature of the composition’s rhythm matched by the necessarily mechanized nature of the movement, is to me, the most significant aspect of Lunn’s piece. I may be completely off-base here, but as I watched the dance evolve I sensed that Lunn’s dancers were the “ghosts in the machine” (particularly since many, if not all, of them appear to be wearing emotionless masks), with the factory machines being a metaphor for the wheelchair machines that drive their motion – with the collateral point being that these people confined to their own machines are not faceless “ghosts.” At this point, I thought Lunn’s concept was brilliant, and that the company’s dancers (Krishna Christine Washburn, Michelle Mantione, Luisa Righeto, Alejandra Ospina, Leslie Freeman Taub, Luznerida Rosado, and Lunn) did a wonderful job conveying Lunn’s concept.

The only part of the dance that I could not explain was its “second half.” As Ravel’s composition ends, a man runs toward the stage from the back of the audience, blowing a whistle presumably signaling that either it’s time to get back to work, or to stop working. This “factory foreman” (played by Richard Daniels) then sees the movement unfold in front of him (part of Ravel’s composition is replayed), or feels its beat as compellingly as the others, and eventually joins the machine-inspired movement on stage until the score runs its course. If there was a point to this addendum aside from obviously binding the dance to its factory setting, I missed it.

In the previous example of her work that I saw a few months ago, Magnetic Temptations, Cook-Beatty choreographed nothing less than a battle for a person’s soul. I found the dance overly long and repetitious (though necessarily so), but was impressed with her energy-driven style that combined lyrical and balletic sensibilities with a contemporary edge, as well as the epic panorama of her subject. Mahaway: Spring Eternal is similarly epic, but it’s broken down into smaller component parts, and consequently, despite what appears to an outsider to be a strange subject, is much easier to digest.

Created in 2013, Mahaway: Spring Eternal is based on a Mayan folk-tale: “The Jaguar and the Little Skunk.” The story tells of a community of skunks, one of whom, the Mother Skunk, has a child. The community is watched over by a Jaguar, known as the skunk community’s Godfather. One day, Godfather Skunk (called Ix Chel) asks Mother Skunk (Akhushtal) to let her child accompany him and older members of the Skunk Community on a hunt. [In some versions of the story, the child is a son – in the dance the child is a daughter; and in some versions the Jaguar and the Baby Skunk go on the hunt alone.] The Jaguar asks the Baby Skunk (Mahaway) to awaken him when she sees a large Antelope. She sees one and awakens the Jaguar, who thereupon kills the Antelope to feed the Skunk Community.

When the season ends and the community’s food is nearly gone, Mahaway asks her mother to let her hunt for food herself (the Jaguar is out of town on business …). Akhushtal refuses, afraid for her daughter, but Mahaway runs off anyway, convinced that she alone could kill the Antelope and provide food for the community, just as Godfather Jaguar did. She eventually finds a huge Antelope and attempts to kill it. But Mahaway is not the hunter that the Jaguar is, and the Antelope kills her. When the Jaguar returns, the community looks for Mahaway, and eventually the devastated Mother Skunk finds her daughter’s body. The moral of the story: don’t bite off more than you can chew (or, listen to your mother; or, don’t go off into the woods without a sharp-clawed godfather jaguar by your side; or, all of the above).

You might think that there’s not enough to this little folktale to fill a dance, but you’d be wrong. Cook-Beatty compartmentalizes the story (without sacrificing visual continuity – there are no gaps), creating six scenes for an Act I, and seven for an Act II, while expanding the sense of each scene to provide the dance with much more depth than does the bare story alone. And to avoid the negative cultural connotations that a dance based on a community of skunks might engender (which obviously the Mayan community didn’t share), the dance – unintentionally – provides a way to circumvent that. As superbly costumed by Zoe Alexander, whose vision made all the character types come alive, these skunks looked at times a bit like raccoons; at other times like squirrels. I’m partial to squirrels, so that’s what I saw – I figured the Mayans wouldn’t mind.

The dance’s story is told in a primitive fashion, like a folk-tale. There are no Disney-ish bells and whistles to elevate the story into something it’s not, but what’s there tells the tale in a simple, and moving fashion. And it’s a modified version of the piece that premiered six years ago: in keeping with the evening’s theme, Cook-Beatty has augmented the Skunk Community, taking it beyond the eight dancers in her own company by integrating five members of Infinity Dance Theater, and further adding eleven “guest artists” selected by audition from the NYC dance community. The result is a diverse community that looks like a diverse community rather than a group of dancers representing one. Despite (or maybe because of) its primitive qualities, it was credible. And the movement created in these community scenes, though not as polished as one might expect in a contemporary dance presentation of this depth, is appropriate for what it’s supposed to be: a community of squirrels. I mean skunks. They jump up and down a lot, move around the stage a lot, assemble and separate a lot, celebrate a lot, and mourn together a lot. It’s not fancy, but it’s also not fake.

To the extent these animals take on human qualities, it’s evident in the more intimate scenes. The two Antelopes (Sasha Rydlizky and Timothy Ward) are relatively wooden, but that’s the nature of their roles. On the other hand, the Jaguar, danced by Niccolo Orsolani, is a feral force of nature. The emotional nuances spring primarily from Akhushtal (Fiona Oba) and Mahaway (Carolina Rivera), who successfully and effectively communicate the folktale’s traits of maternal concern, youthful over-confidence, and despair. Vera Paganin, Jacob Brown, and Richard Sayama were the other Alison Cook Beatty Dance cast members.

Folktales like this are often limited to productions by “children’s theater.” There’s nothing wrong with that. But Mahaway: Spring Eternal is a level above that. And as noted above, the dance was created to commemorate the centennial of The Rite of Spring, and if the dance’s subtitle (“Spring Eternal”) and folkloric story weren’t by themselves sufficient allusion to the landmark Stravinsky / Nijinksy piece, the accompanying score by Dorian Wallace occasionally mimics iconic moments from Stravinsky’s composition to drive the point. The presentation was further enhanced by a live performance of Wallace’s score by a group called Tenth Intervention (Lynn Bechtold, Mioi Takeda, Carrie Frey, Ellery Trafford, Borah Hahn, and Sam Bae).

The evening concluded with Pietà, a solo for Lunn that is dedicated to the memory of her late husband, Andrew Macmillan. With the accompanying music, Be Still My Soul (sung live, and movingly, by baritone Jim Trainor – accompanied by Bae on cello and Hahn on piano), the piece was an effective and moving tribute.

Prior to the performance, while I waited for the theater’s doors to open, I sat within what effectively is the lobby. While there, I observed a frenetically fluttering butterfly that had made its way through the church and into this lobby area. As it flew by (several times), I thought that perhaps it wasn’t a butterfly, but only a moth that looked and moved like a butterfly. After Ghosts in the Machine ended, as intermission began, I started walking back into the lobby area, and on my way out spied that same moth that looked like a butterfly, who apparently found the theater as welcoming as the lobby. Maybe it just wanted to see the show, or prove that it could.

I suppose, if nothing else (and there’s a lot “else”), this “Ghost in the Machine” program demonstrates that just as moths that aren’t supposed to be butterflies can be butterflies, persons who aren’t supposed to be able to dance can dance.

Author: Jerry Hochman

Source: https://criticaldance.org/skunks-and-squirrels-moths-and-butterflies-and-ghosts/