Alison Cook Beatty Dance

The Ailey Citigroup Theater

New York, New York

March 13, 2023

10th Anniversary Program: Joyful Offering, Touched By Fire, One More Day, Lifeline, Absurd Heroes, Central Park Field #4, Seele, Houston Street Hootenanny

Jerry Hochman

I sometimes tell curious people that I attend dance performances religiously. What I don’t usually say is that sometimes these dance performances are the equivalent, to me, of religious experiences: the impact on the heart and soul of a particular performance or program can, at rare times, be inspirational. So it was with Monday night’s twice-delayed 10th Anniversary performance of Alison Cook Beatty Dance.

The first delay was a consequence of the Covid pandemic. The second was a performance at New York Live Arts last November that was suddenly interrupted when its Board President, Gerald Appelstein, collapsed while introducing the next dance on the program, One More Day, which was choreographed to a poem he’d written regarding the death of a member of his family (which I still don’t feel comfortable discussing in detail). What happened afterward is documented in my subsequent account of the evening: https://criticaldance.org/alison-cook-beatty-dance-yea-though-i-walk/ .

Especially in light of the previous attempt, Monday night’s program wa

(front; center)

and Alison Cook Beatty Dance

in last November’s performance

of “One More Day”

Photo by Rob Klein.

s indeed a celebration. While Appelstein himself wasn’t there (he’s still recovering, but, the audience was told, is doing well), in other respects the evening proceeded as intended – to be a celebration of Alison Cook-Beatty’s choreography and of Alison Cook Beatty Dance’s 10 year history. Overall – and even though the full house audience at the Ailey Citigroup Theater very obviously would have expressed their appreciation for each piece on the program regardless of its merits – the program was highly successful for Cook-Beatty and her company, displaying the remarkable breadth of her choreography over the years as well as the individual and collective talents of the company’s dancers.

I’ll address the program seriatim, briefly discussing the seven of eight dances I’d previously seen and reviewed, then focusing in more detail on the closing piece, the only one I’d not previously seen in whole or in part.

The evening began, as it did last November, with Joyful Offering, one of Cook-Beatty’s finest and most accessible pieces. The subject is pure and simple joy – not necessarily of something, but of being. The dance could have been one-dimensional, but, again, Cook-Beatty’s choreography (here to J.S. Bach’s Oboe d’amore in D Major Allegro I and III) takes full advantage of the baroque complexity and warmth of the composition to create an equally complex, choreographically varied, and thoroughly engaging dance celebration.

in the premiere performance of “Joyful Offering”

Photo by Russell Haydn

In addition to an abundance of smiles, much of the dance’s imagery is highly emphasized arm movements, either fully extended or slightly rounded upward while the piece progresses, that bear a fleeting resemblance to characteristics of Paul Taylor’s choreography, but that’s only one type of a multitude of celebratory images that appear as inevitable consequences of a visualization of Bach’s music. And Joyful Offering is focused exclusively on joy, with no interfering emotional components. The feeling is both intoxicating and contagious, and the dance fills the performing space and the audience with good cheer.

The second dance, Touched by Fire, is the oldest of Cook-Beatty’s choreography on the program (from 1998), I’ve seen it twice before – in November, and before that performed as a duet with a wheelchair-bound dancer. It was unusually moving on both prior occasions, and remains so here. Performed again with Jisoo Ok on cello, Touched by Fire is not an unusual type of solo by a nascent dancer/ choreographer, but, as I observed previously, it has flair and a compelling sense of leaving the past behind to pursue an unknowable but essential future.

As in November, this piece was followed by introductory comments, this time from Appelstein’s sister and by Dionne C. Monsanto, Loss Survivor, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention National Chapter Leadership Council (whose daughter, who died by suicide, had a scholarship at Ailey and had danced on that stage) – the organization, and cause, to which the performance was dedicated.

with Jisoo Ok on cello

Photo by Rob Klein

One could almost hear the audience sigh in relief as the addresses concluded without incident. This time, finally, the performance proceeded as planned.

One More Day has taken on a life of its own since I first saw it at its premiere a year ago, almost to the day, before this performance. Although it’s one of many high-caliber dances choreographed by Cook-Beatty and performed by her company, it’s a gem that maintains its power no matter how frequently it’s seen, and may well become one that audiences demand to see in future programs.

Alison Cook Beatty Dance

in the premiere performance of “One More Day”

Photo by Paul B. Goode

The dance is choreographed to a composition, If I Had One More Day by Polina Nazaykinskaya and Konstantin Soukhovetski, based on a poem by Appelstein, and here performed live by Soukhovetski on piano and passionately sung to Appelstein’s lyrics by Broadway singer Jeff Keller. The poem is a “grief” poem – reflecting and relating the torment one feels after the death of another: the inconsolable need for “one more day.” The dance is a dance of grief too, but the simplicity of the music combined with the anguish of the words create tension between memory and agony that the dance replicates and translates into a physical struggle and heart wrenching spiral of uncontrollable emotions.

The subject of the death of a child has been considered in many previous dances, including some created by highly celebrated choreographers. But One More Day is different. Here, in the focused simplicity of the words, the music, and the choreography, the death is not seen from a distance; it has an immediacy, as well as a sense of helplessness, that other such dances that I’ve seen lack. What it doesn’t have is a sense of guilt; self-blame or similar responsibility for what happened. It’s simply about loss: nothing more; nothing less. And it’s told in a manner that makes the subject at once personal and universal: knowing what happened here makes it highly individual, but the dance works on a broader canvas, capturing the terror and despair prompted by a sudden and unexpected tragedy that transcends its immediate inspiration.

Photo by Rob Klein

As fine as the words, music, and choreography are, One More Day wouldn’t register as vividly as it does without the execution by seven of the company dancers, including most notably Jacob Blank as the departing soul, and Mariah Anton Arters as his mother. [When I first saw the piece, without knowing the details of its genesis, I saw Anton Arters’s character as his wife. It works on either – or any similar – level.] Anton Arters, the senior member of the company, is the focus of attention (to the extent there is one) in many of the dances on this program. Here, however, she delivers (and has each of the other times I’ve seen the piece) a performance that’s as immediate, compelling, and ultimately shattering as anything else I’ve seen in dance where such emotions are appropriate, going far beyond what one might reasonably consider to be dance/ theater acting without becoming in any way melodramatic. I rarely describe any performance as “perfect,” but this one is.

Two of the evening’s dances were performed by guests who wanted to help celebrate the occasion. One of these dances, her 2001 piece Lifeline, is a far better pas de deux than one had any right to expect from a choreographer who, at the time, was still a student at The Boston Conservatory.

in Alison Cook-Beatty’s “Lifeline”

Photo by Russell Haydn Photography

To compelling music by Karl Jenkins (Adiemus Variations I-III), guest dancers Tara Bellardini and Amar Smalls (both with Ailey School and/or Ailey II connections) sailed through this “relationship dance.” Although the subject, especially including the couple eventually appearing to go their separate ways, is tired at best, here there’s a freshness to it contributed both by Cook-Beatty’s youthful take on the subject (there’s no sense here of “by the numbers” choreography), the simplicity of her choreography (which, as I previously observed, is a virtue), combined with the dancers’ performances. There’s little here in the way of characterization (what little there is was contributed by Bellardini, together with her crystalline execution); indeed, the couple’s demeanor throughout was relatively stoic. But the dance’s choreographic variety (including leaps and lifts that describe high-points in the relationship) contributes sufficient emotions, albeit passionless, on its own.

The first group of pieces prior to intermission concluded with Cook-Beatty’s Absurd Heroes, which I first saw in at its premiere a year ago and thereafter reviewed in considerable detail. It’s an intriguing and curiously entertaining dance, emphasizing the futility, and nobility, of what, like the legend of Sisyphus, is a struggle for something that cannot be achieved; struggle for its own sake.

in the premiere performance of “Absurd Heroes”

Photo by Paul B. Goode

But, as I previously observed, there’s more here than that. Cook-Beatty has used for her score a piece by American “post-minimalist” composer David Lang, titled Mountain, which includes pounding, piercing sounds like missiles striking their targets, followed by melodic sounds that grow in intensity like a prolonged wail. With this score as its framework, Cook-Beatty and her dancers visualize not only the perpetual challenges of everyday life, but those overwhelming forces that eternally seek to destroy life because the lessons of history are never learned.

The struggles are visualized as a series of endless pushes and pulls, of a tug of war between two groups of dancers, of attempts to escape from some sort of confinement, and of looking for a way out that isn’t there. Cook-Beatty is not here condemning these “absurd heroes” who fight against forces that they can’t overcome; rather, I think she’s celebrating them as true heroes, but in a perpetually losing battle.

Photo by Rob Klein

With current events in the mind’s background, Absurd Heroes came across at this performance as even more memorable and powerful than it did when I previously saw it. And to an extent, the dancers here, with Anton Arters and Genaro Freire providing especially vivid portrayals, assumed the roles of absurd heroes themselves – not only as stand-ins for others, but for being able to get through this physically demanding dance.

Following intermission, the company (also including visiting alumnae) presented Cook-Beatty’s Central Park Field #4. The program indicates that what was presented was an excerpt, but whatever it was appeared far more extensive than an earlier presentation that I saw in an October, 2021 program. But even if that’s simply a product of aging memory, the piece as presented here looked even better than it did before.

of “Central Park Field No. 4”

Photo by Russell Haydn

Cook-Beatty created Central Park Field #4 during the pandemic. Unlike most other dancers and choreographers who confined their pandemic creations to their confines – apartments or house rooms via Zoom or TicTok together with other similarly confined company dancers or friends, Cook-Beatty created outdoors where the people were (at least those who ventured outdoors), on a baseball field in Central Park. That’s not to attach a value judgment to the indoor creations – some that I saw were quite good – but Cook-Beatty chose not to emphasize the pandemic confinement, but to use its consequences as a creative opportunity.

When I last saw this piece, indoors but after the pandemic had eased to the point where some indoor performances were not prohibited, a backdrop on which the actual Central Park Field #4 was projected provided the ambiance. Here, that projection was eliminated, leaving only an artificial infield with bases taped onto the stage floor. One would think that a certain verisimilitude would have been lost, but that wasn’t the case. To my eye, performed on a “field” of sorts and without any other distraction, somehow made Central Park Field #4 look less artificial.

Photo by Russell Haydn

Perhaps as a consequence, the piece itself looked more substantial on this viewing. One could concentrate on the choreography and the music rather than the setting. The same slow-motion opening began the piece, with dancers evoking nostalgic images of “real” people having played baseball on that field setting the stage, or the field, for something more than recovered memories. Soon the piece morphed into more rapid-fire dance movement that merges the baseball imagery with varied, intricate and fast-paced choreography, all while maintaining a sense of the baseball or softball theme (considering that the dancers wore pinstriped baseball uniform-like costumes – designed by Ali Taghavi – it would have been difficult not to). And, no doubt in large part as a consequence of the Philip Glass score (Concerto No. 2 for Violin and Orchestra; “The American Four Seasons”), at times I saw fleeting choreographed images that brought to mind Twyla Tharp’s masterpiece In the Upper Room.

As I wrote previously, Central Park Field #4 combines wistfulness with a sense of joy, and includes considerable – and given the subject matter, surprising –choreographic variety. So not only is it a pandemic memento, it’s also a highly entertaining dance.

The dance that followed, Seele, was performed by guest artists from White Wave Dance: Mark Willis, Lacey Baroch, and Casey LaVres. The dance is a pas de trois with two women and one man where the visualized relationship involves complex emotional currents that ultimately make it difficult to determine where the center of gravity is, or if there is one. It’s a dynamic and somewhat mysterious piece; one doesn’t know exactly what the motivations behind the dancers’ actions are.

in Alison Cook-Beatty’s “Seele”

Photo by Russell Haydn

In a brief description that I don’t recall seeing previously, Cook-Beatty states that the dance “explores the complexities of the human psyche through an abstract presentation of the id, ego, and superego – performed as a trio.” While Seele (which means “soul” in German) definitely includes actions reflecting the complexities of the human psyche, I find those concepts difficult to see in the dance itself, which, because of the way it’s structured, shows a battle of sorts between three distinct but individual characters. While the two women, in what are essentially identical costumes, can be seen as representing different personality components struggling for domination over the male dancer, whether for sexual dominance or for his soul, I don’t see within the dance itself that the two women represent competing forces of the man’s personality. But then, perhaps I’m too concrete, and the dance requires more of a leap of logic than I can muster. Whichever way it’s described, however, it’s still a curiously entertaining enigmatic and emotionally-charged, albeit low decibel level, dance.

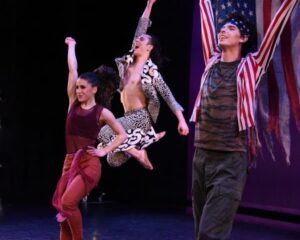

The evening’s closing piece, Houston Street Hootenanny, was choreographed in 2013 while Cook-Beatty was teaching at the Joffrey Ballet School in Greenwich Village, which commissioned the dance. To me, the dance is problematic on several levels. Nevertheless, these concerns, which I’ll briefly address below, ultimately are irrelevant, and pale in comparison to the impact that the dance itself has. It’s a huge success, and far better at characterizing its period of music/ social history than other similar such pieces created by far more experienced choreographers; a period that neither the choreographer nor any of the dancers, and few in the audience, had actually lived through.

My first nitpicky concern is the dance’s title. In her introduction to the dance (also used as an opportunity to thank those who contributed to the celebration’s rescheduling, specifically including Robert Battle, Artistic Director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, who enabled the performance to take place where it did), Cook-Beatty said that an indicator of the 60s, the subject time period of the dance, was known for its “happenings,” and that one such happening was a hootenanny.

Well, no. They’re not the same thing, and one isn’t a subset of the other. A happening, in the 60s (the term was actually coined in1958) related to unique, largely improvisational events that can pop up anywhere, and require active participation by spectators. A hootenanny was not the same thing. It’s an older term that, in this context, was more of a staged concert or public performance that didn’t involve audience participation. Regardless, the term was effectively killed by a TV show called “Hootenanny,” in ’63 and ’64 or so, that focused on folk-pop music (The Limelighters, The Chad Mitchell Trio, The New Christy Minstrels, Johnny Cash …) initially taped on college campuses, but it wasn’t the type of counterculture folk music that Cook-Beatty is focusing on in the dance. More importantly, serious counter-culture folk singers were reportedly blacklisted for fear of some public backlash, and in turn the TV show was boycotted by them. The program died relatively quickly, and I don’t recall the word ever being used again. And Houston Street has nothing to do with anything counter-culture during that time period – but admittedly it carries a certain zing placed next to Hootenanny. The center of folk/ counterculture in NYC was then in Greenwich Village and the East Village.

Photo by Russell Haydn

My second admittedly spurious criticism is that the music selected is strange. The dance and music as a whole focus on counter-culture, but the piece opens with Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Sound of Silence,” – a great song, though more urban (New York)-centered than folk. Be that as it may, it made sense to include it. But after a couple of stanzas, a different version of the song replaced the original. This version, sung by Disturbed, wasn’t released until 2015, and converts Simon’s poetry and matter-of-fact sadness into an extended wail and post-millennium angst-ridden rage. That’s valid, and the song is very moving sung this way, but what’s it doing here?

And then, as the dance segues into its folk music/ hootenanny-ish mode, it uses two songs by Joan Baez. She certainly qualifies for inclusion, but the songs selected, “Te Ador/Ate Amanha” and “Plaisir D’Amour,” are among her most obscure. In view of the protest songs that follow them, wouldn’t “We Shall Overcome” or “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” have worked equally well, and/or, if a slow-paced love song was deemed necessary at that point in the dance, for period accuracy why not Judy Collins’s cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne”?

But neither of these areas are really valid criticisms – just rants by one who lived through the 60s. And even if the visualization here is more Haight-Ashbury than Greenwich Village (with a little Woodstock thrown in), it is what it is. And on its own terms, Houston Street Hootenanny works very well in capturing the spirit of folk music/ counterculture of the 60s in whatever venue one chooses to put it, especially the remaining songs in the piece: Richie Havens’s “Freedom,” Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” and Peter Paul and Mary’s “If I Had a Hammer.” Indeed, in view of unnecessarily apologetic comments about the use of a tattered American Flag in her introduction to the piece (and an apologia in the program along the same line), the thrust of what Cook-Beatty really wants communicate, and successfully does, in addition to depicting the time period, is that none of the counter-culture folk music / social commentary / injustice songs of the 60s could have happened had rights allowing such freedom of expression not existed in the United States.

The spirit of the time in the piece, its innocence (and maybe naivete),

in “Joyful Offering”

Photo by Rob Klein

social consciousness, and joy of

like-minded comradery (even a barely perceptible nod to the sexual revolution) is conveyed not only by the generally jubilant choreography and the captivating execution by the company’s dancers (and a few alumnae), but also by the costumes (designed by Tony Musco) and the occasional musical accompaniment to one or two of the songs played live on tambourine and makeshift percussion and in character by Michael Feigenbaum.

Without doubt the “star” of the evening was Cook-Beatty’s choreography; such a breadth of choreographic variety at such a relatively early stage in a choreographic career is quite exceptional. But credit must also be extended to the company’s dancers – an eclectic but talented group that communicated the essence as well as the details of Cook-Beatty’s choreography with a seemingly unlimited combination of boundless energy and abundant artistry. In addition to Anton Arters, Blank, and Freire, the company dancers included Madelaine Burnett, Joanna Ioannides, Madeline Kuhlke, Payton Primer, and Tomislav Nevistic. The alumnae guest artists were Miranda Stuck, Nika Antuanette, and Vera Paganin, and founding member Lindsey Miller.

Last November, I titled my chronicle of that ultimately cancelled 10th Anniversary performance with a brief quote from the 23rd Psalm: “Yeah though I walk.” With its 10th Anniversary performance finally completed, Alison Cook Beatty Dance can confidently declare, without hesitation, that that their cup runneth over.

By Jerry Hochman of Critical Dance

Source: https://criticaldance.org/alison-cook-beatty-dance-their-cup-runneth-over-2/